Hidden deep within the millions of nephrons working tirelessly daily is a medical mystery called FSGS – Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. A rare but challenging form of glomerular disease, microscopic sclerosis silently occurs within each filtering unit.

FSGS is not a flashy presence. It quietly drains protein into the urine, causing swelling, increasing blood pressure, and eventually – if left unchecked – leading to kidney failure. Its onset is often unannounced, but the consequences are lifelong.

Decoding FSGS is a journey into the core of kidney physiology – where small abnormalities can lead to serious biological consequences.

FSGS kidney disease is a rare but serious condition that affects kidney filters.

What is FSGS Kidney Disease?

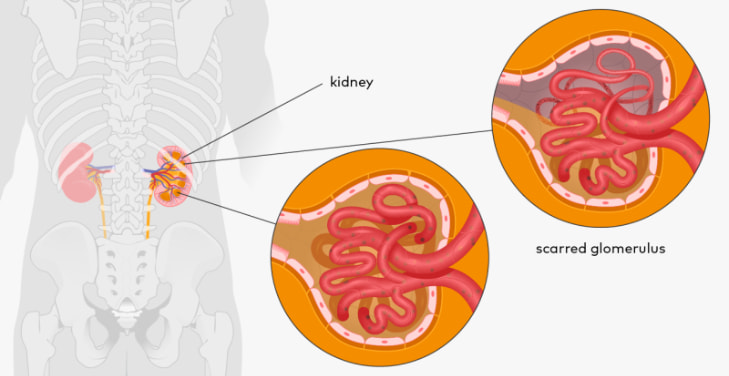

FSGS – short for Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis – is a chronic glomerular disease that causes scarring of a portion of the kidney’s filtering units (called glomeruli). It is not simply a disease – it is a complex, insidious syndrome and often progresses so quietly that it is not recognized until the damage is severe. For many people, FSGS is a diagnosis that marks a major turning point in their lives.

Explaining the name: Medically significant words

- Focal: refers to some – but not all – glomeruli being affected.

- Segmental: the scarring does not spread to the entire glomerulus but only to parts of it.

- Glomerulosclerosis: the fibrosis – that is, scarring – causes the glomeruli to lose their filtering function.

How does FSGS affect the kidneys?

Your kidneys act like magical filtering machines – removing waste balancing fluids and electrolytes. When the glomeruli become scarred, protein leaks from the blood into the urine (proteinuria), leading to swelling, high blood pressure, fatigue, and, if left unchecked – kidney failure. Some forms of FSGS progress slowly, but others progress very quickly, even leading to end-stage kidney failure in just a few years.

The danger is: that no two people are alike

Every FSGS patient has a unique story: some have genes, some have a virus, and some never know why. And because of this diversity, there is no one-size-fits-all treatment for FSGS.

Causes of FSGS

FSGS is a kidney disease that is essentially a painting painted by many different hands – each cause leaves its mark on the delicate structure of the kidney. It is not easy to find the culprit initially because the disease process can last silently until obvious symptoms appear and the damage has already formed.

Primary FSGS

In many cases, the disease occurs without a clear cause being found. This is the primary form – a phenomenon in which the immune system can break down the glomerular filtration barrier. Small molecules, which can be circulating factors or inflammatory signals, are thought to be the agents that disrupt the filtration structure – causing protein leakage causing small pieces of fibrosis in the blood filtration system.

Secondary FSGS

Obesity causes increased intraglomerular pressure, which leads to damage over time.

Viruses such as HIV or hepatitis B/C can initiate a prolonged inflammatory response.

Nephrotoxic drugs, including heroin, lithium, or anabolic steroids, can be a catalyst for damage.

Genetic factors: gene mutations that affect the structure of podocytes – the key cells in the filtering process.

FSGS is not simply a consequence. It results from multiple attacks – silent but persistent – on the body’s most sophisticated filtering system.

Symptoms of FSGS

FSGS does not knock on the door with a bang. It creeps in, silently destroying the kidney structure, and then one day, the patient is shocked when the body speaks up. The symptoms of FSGS are a multi-faceted picture - sometimes loud, sometimes so faint that they are ignored. However, each sign is an urgent signal from the kidney, calling for attention before the damage becomes permanent.

Proteinuria

The appearance of protein in the urine, often discovered by accident during testing, is the earliest and most characteristic symptom. When dialysis leaks, protein - which should stay in the blood - flows out. The patient may see more foamy urine, even like soap.

Edema

Swelling of the feet, ankles, and around the eyes - is a consequence of protein loss, leading to water retention. Some patients wake up with a puffy face, others find their shoes are unusually tight at the end of the day.

Fatigue, weight gain, high blood pressure

Lack of protein, water retention, and high blood pressure all create a feeling of heaviness and constant fatigue. The weight may be increasing rapidly, but it’s not fat – it’s fluid, accumulating day by day.

FSGS doesn’t sound alarm bells. But your body does – and you need to listen.

How is FSGS diagnosed?

Diagnosing FSGS is not a single step but a journey of dissecting each layer of clinical, paraclinical, and histological manifestations. Because FSGS has no specific symptoms initially, disease identification requires close coordination between clinicians, nephrologists and pathologists – each a piece of the final diagnostic puzzle.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis is the first gateway. Proteinuria – especially high levels of urine – is a red flag. Occasionally, fatty casts or deformed red blood cells may be seen, indicating deeper glomerular damage.

Blood tests

Kidney function is assessed by creatinine, BUN, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Low serum albumin levels and lipid disorders are also present due to the kidney’s inability to retain protein and regulate metabolism.

Kidney biopsy

There is no substitute for a kidney biopsy. Under the microscope, the doctor can see individual areas of sclerosis in the glomeruli – small fragments and scattered lesions. This is the “final” evidence, confirming the diagnosis of FSGS, and also helps distinguish between different types of the disease.

Diagnosing FSGS is not based on emotions. It is a logical, meticulous process that cannot be rushed. Because each case is a map – and the kidney is a territory that needs to be carefully explored.

Types of FSGS

FSGS is not a single entity but a syndrome - a collection of many types of lesions with different formation mechanisms, leading to the same outcome: partial glomerulosclerosis. The classification of FSGS is not formal but plays a key role in prognosis and treatment options. Each type is a pathological variant, a unique identity in the picture of kidney damage.

Primary FSGS

The primary type is usually the result of an immune disorder or an unidentified plasma factor that directly attacks the podocyte cells - an important filtration barrier in the glomerulus. The manifestations are often dramatic, with typical nephrotic syndrome, high proteinuria, and systemic edema.

Secondary FSGS

Originating from exogenous factors such as obesity, viral infection, toxins or underlying diseases that increase filtration pressure in the kidney, leading to secondary damage. Proteinuria is often milder, edema is rarely severe, and responds poorly to immunosuppressive drugs.

Hereditary FSGS

Associated with genetic mutations affecting podocyte structure or function. Usually seen in children, early onset, slow progression but unresponsive to immunotherapy. Genetic testing is the key diagnostic tool.

Collapsing variant FSGS

The most aggressive form, rapidly progressive, with extensive fibrosis. Glomeruli collapse under the microscope, rapidly progressing to end-stage renal failure. Often associated with HIV or APOL1 mutations in people of African descent.

Not all FSGS are the same. Understanding the type is the first step to individualizing treatment and preserving each precious filtering unit in the kidney.

Treatment options for FSGS

Treatment of FSGS is a balancing act between controlling symptoms, preventing further damage, and preserving kidney function for as long as possible. There is no one-size-fits-all approach – FSGS is a syndrome with many causes and manifestations. Doctors treat not just the tests but the person behind the condition.

Immunosuppressants

Corticosteroids such as prednisone are the first line of treatment for primary FSGS. If the condition does not respond, calcineurin inhibitors such as cyclosporine or tacrolimus may be added. The goal is to calm the immune response that attacks podocytes – the important cells in the filtration barrier.

Control blood pressure and proteinuria

ACE inhibitors or ARBs lower blood pressure and reduce protein leakage through the kidneys – one of the main factors that cause fibrosis. This is the cornerstone of treatment for all patients with FSGS, regardless of the cause.

Lifestyle

A low-salt, low-protein diet, weight control, and blood sugar control help reduce the kidney burden. Regular exercise and stopping harmful medications are sustainable steps in long-term management.

Advanced cases

When kidney function is no longer salvageable, dialysis or kidney transplantation are the last options. However, FSGS can recur after transplantation – and this is a major challenge that medicine is still trying to overcome.

Treating FSGS is a balancing act – between attack and conservation, medicine and lifestyle, and between expectations and biological reality.

Prognosis and progression of the disease

FSGS is a journey whose starting point is never the same, and the destination is unpredictable. The prognosis of the disease does not depend on a single variable. Still, it results from the interaction between the disease type, the extent of histological damage, the response to treatment, and even the underlying genetic factors. Some people live with the disease for decades, stable, while others have rapid renal failure within a few months of detection.

Depending on the disease type and the level of response

Primary FSGS can respond well to corticosteroids if detected early, but if resistant, the risk of progression to chronic renal failure is very high. Meanwhile, hereditary FSGS often does not improve with immunotherapy, leading to a slow but irreversible decline in renal function. The collapsed form progresses rapidly, often leading to dialysis within a few months.

Warning signs and risk factors

Prolonged proteinuria >3.5 g/day, profound hypoalbuminemia, resistant hypertension, and rapid decline in eGFR are poor prognostic indicators. Carriers of the APOL1 gene variant (especially those of African descent) are at a much higher risk of developing renal failure.

The progression of FSGS is a steep slope—it can be gentle or steep. Slowing each step of that slide requires close monitoring, proactive treatment, and long-term collaboration between patient and physician.

Living with FSGS

FSGS does not end after diagnosis. On the contrary, it is the beginning of a journey of living with the disease – where the patient becomes an active health manager, facing challenges that are not always visible but simmer in each index, each time of unexplained fatigue. Living with FSGS is not a sentence but a long-term negotiation with one's body.

Close monitoring and treatment compliance

Maintaining a regular schedule of follow-up visits and periodic urine, blood, and blood pressure tests is the foundation of disease control. Missing a small sign can be exchanged for a stage of kidney failure that is difficult to recover. Adhering to the regimen – however complicated – is a shield against silent progression.

Nutrition and lifestyle habits

A low-salt, moderate-protein diet, and cholesterol control are indispensable therapies. Sleep, gentle exercise, weight control, and avoiding chronic stress help reduce the metabolic burden on the kidneys – although these are less measurable in numbers.

Psychology and emotional support

FSGS is not only physically devastating, it is also psychologically corrosive. Anxiety, loss of control, and even depression are common. Connecting with a support group, psychologist, or patient community helps patients not feel alone in their fight.

Living with FSGS means living with a body that changes – not by the day, but by the year. But with knowledge, discipline, and faith, patients can completely rewrite the quality of their lives.

FSGS in children versus adults

FSGS does not discriminate by age. But how it starts, progresses, and responds to treatment in children takes a very different form than in adults. The same glomerular lesions, the same proteinuria, and edema, but behind them are separate biological, genetic, and clinical mechanisms - forcing doctors to "read" the disease in two different languages.

Early onset, suspected genetic factors

In children, especially those under 6 years old, FSGS is often associated with gene mutations that affect podocyte structure, such as NPHS2, ACTN4, or WT1. These genetic forms are often resistant to immunosuppressants and progress chronically. In contrast, in adults, most FSGS is primary or secondary to factors such as obesity, hypertension, or viral infections.

Differences in treatment response and prognosis

Children have a better chance of recovering glomerular structure, but once renal failure occurs, it progresses more rapidly than adults. Early detection and genetic testing are vital for long-term management. In adults, treatment response depends largely on the extent of histological damage and can be better managed with early treatment.

FSGS in children is not a miniature version of the disease in adults. It is a distinct entity that requires a comprehensive individualized strategy – from diagnosis and treatment to long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

FSGS is a complex glomerular disease with diverse causes, manifestations, and prognoses. Each case is a separate biological structure, requiring meticulous understanding to avoid incorrect interventions with long-term consequences.

Early diagnosis, accurate classification, and individualized treatment are key to disease control. Multidisciplinary coordination, from nephrology to genetics and clinical psychology, will allow patients to live healthier lives.

FSGS does not mean kidney loss if there is a proactive and persistent strategy from both doctors and patients.

Frequently Asked Questions About FSGS (Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis)

-

Can FSGS be completely cured?

FSGS is not a disease that can be “cured” in the absolute sense but rather a chronic disease that requires long-term control. Treatment goals are to reduce proteinuria, preserve kidney function, and prevent progression. -

Does FSGS recur after kidney transplantation?

Yes. Recurrence of FSGS after transplantation occurs in about 20–40% of cases, especially in the primary form. The mechanism may be related to unidentified circulatory factors, requiring aggressive treatment and close monitoring after transplantation. -

Is FSGS similar to other kidney diseases?

No. FSGS is a distinct form of glomerular damage, often manifested by segmental glomerular fibrosis. Unlike glomerulonephritis or renal lupus, FSGS can progress silently and is resistant to treatment. -

What foods should people with FSGS avoid?

Limit salt, excessive animal protein, and processed foods high in phosphorus and potassium. The diet should be adjusted based on glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria level, and guidance from a nutritionist. -

How long does it take for FSGS to progress to kidney failure?

The rate of progression varies greatly, from several years to just a few months, depending on the disease and response to treatment. Cases that do not control proteinuria and blood pressure well are at risk of early end-stage kidney failure.